|

|

|

James Webb telescope takes super sharp view of early cosmos [size=0.8125]By Jonathan Amos

BBC Science Correspondent

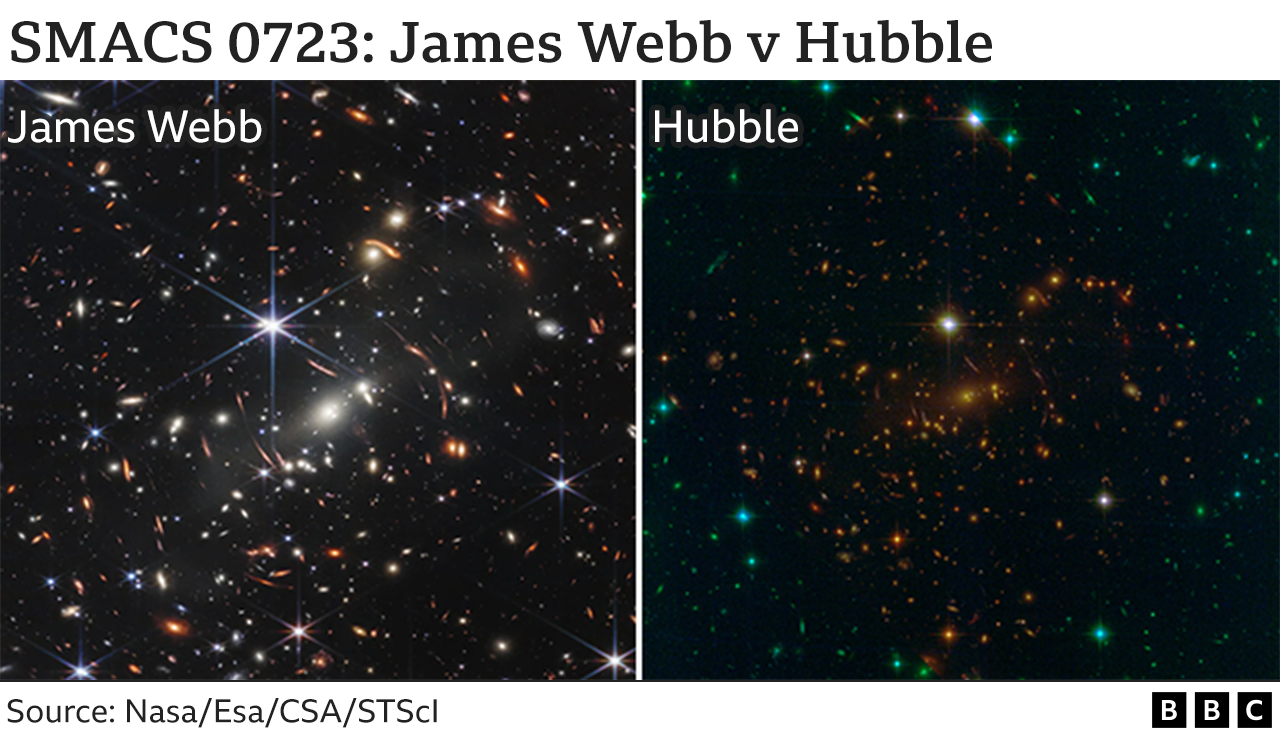

[size=0.75]IMAGE SOURCE, NASA/ESA/CSA/STSCI [size=0.75]IMAGE SOURCE, NASA/ESA/CSA/STSCI

Image caption, SMACS 0723: Red arcs in the image trace light from galaxies in the very early Universe

The first full-colour picture from the new James Webb Space Telescope has been released - and it doesn't disappoint.

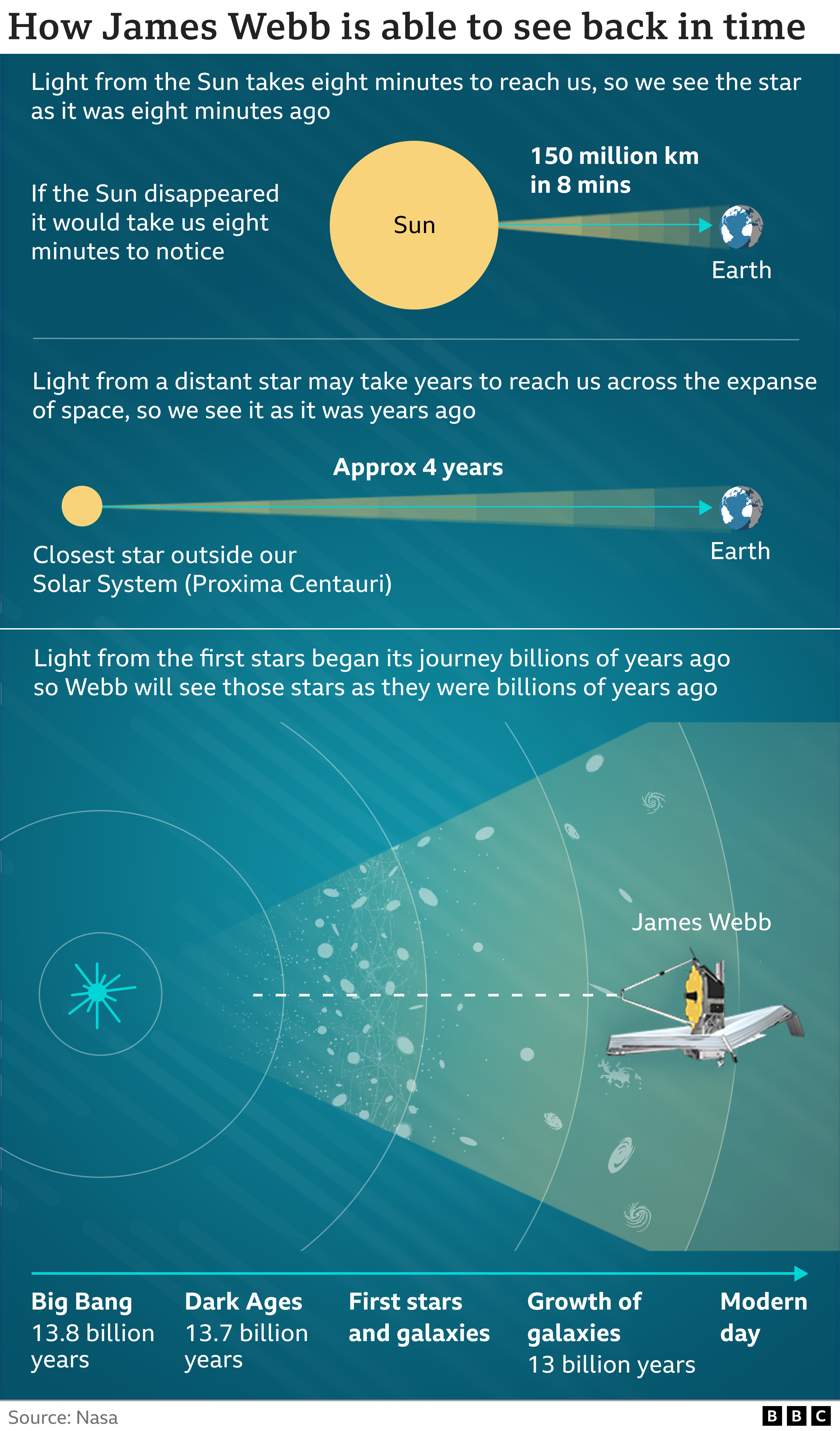

The image is said to be the deepest, most detailed infrared view of the Universe to date, containing the light from galaxies that has taken many billions of years to reach us.

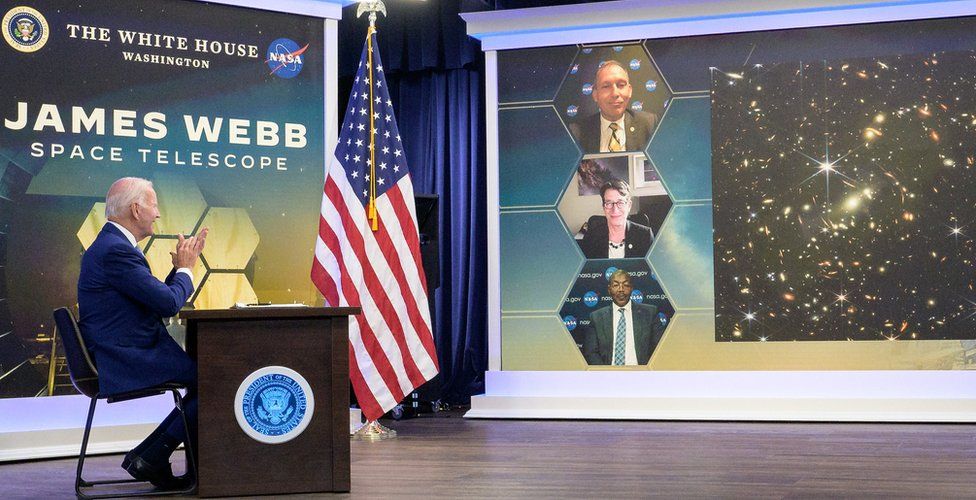

US President Joe Biden was shown the image during a White House briefing.

Further debut pictures from James Webb are due to be released by Nasa in a global presentation on Tuesday.

"These images are going to remind the world that America can do big things, and remind the American people - especially our children - that there's nothing beyond our capacity," President Biden remarked.

"We can see possibilities no-one has ever seen before. We can go places no-one has ever gone before."

[size=0.75]IMAGE SOURCE, NASA [size=0.75]IMAGE SOURCE, NASA

Image caption, President Biden applauds the unveiling of the first full-colour image from Webb

It will make all sorts of observations of the sky, but has two overarching goals. One is to take pictures of the very first stars to shine in the Universe more than 13.5 billion years ago; the other is to probe far-off planets to see if they might be habitable.

The image unveiled before President Biden showcases Webb's capabilities to pursue the first of these objectives.

What you see is a cluster of galaxies in the Southern Hemisphere constellation of Volans known by the ungainly name of SMACS 0723.

The cluster itself isn't actually that far away - "only" about 4.6 billion light-years in the distance. But the great mass of this cluster has bent and magnified the light of objects that are much, much further away.

It's a gravitational effect; the astronomical equivalent of a zoom lens for a telescope.

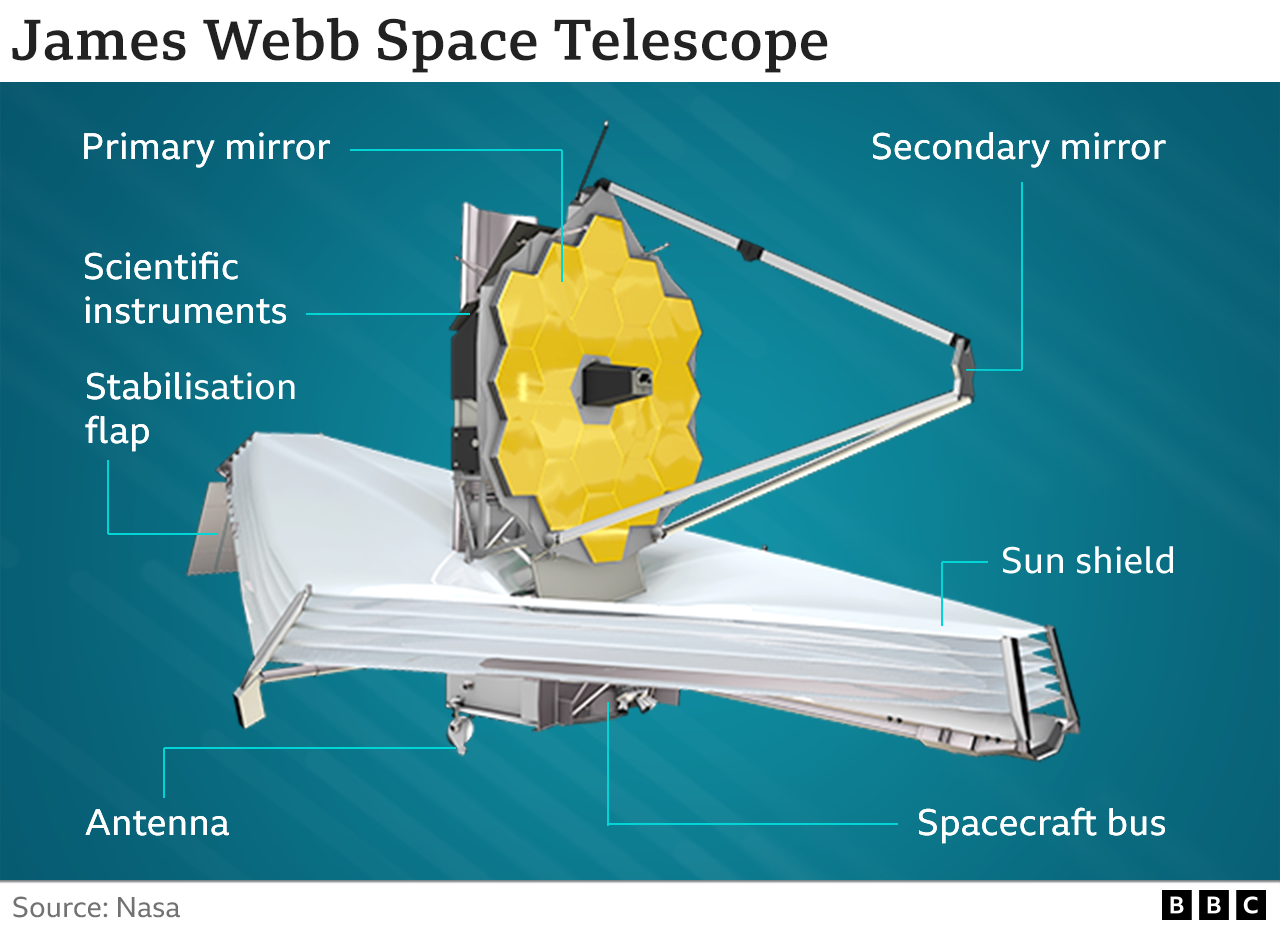

Webb, with its 6.5m-wide golden mirror and super-sensitive infrared instruments, has managed to detect in this picture the distorted shape (the red arcs) of galaxies that existed a mere 600 million years after the Big Bang (the Universe is 13.8 billion years old).

Media caption, Amber Straughn: Why the James Webb telescope sees in the infrared

And it's even better than that. Scientists can tell from the quality of the data produced by Webb that the telescope is sensing space way beyond the most far-flung object in this image.

As a consequence, it's possible this is even the deepest cosmic viewing field ever obtained.

"Light travels at 186,000 miles per second. And that light that you are seeing on one of those little specks has been travelling for over 13 billion years," said Nasa administrator Bill Nelson.

"And by the way, we're going back further, because this is just the first image. They're going back about 13 and a half billion years. And since we know the Universe is 13.8 billion years old, you're going back almost to the beginning."

Hubble used to stare at the sky for weeks on end to produce this kind of result. Webb identified its super-deep objects after only 12.5 hours of observations.

Nasa and its international partners, the European and Canadian space agencies, will release further colour imagery from Webb on Tuesday.

One of the topics to be discussed will touch on that other overarching goal: the study of planets outside our Solar System.

Webb has analysed the atmosphere of WASP-96 b, a giant planet located more than 1,000 light-years from Earth. It will tell us about the chemistry of that atmosphere.

WASP-96 b orbits far too close to its parent star to sustain life. But, one day, it's hoped Webb might spy a planet that has gases in its air that are similar to those that shroud the Earth - a tantalising prospect that might hint at the presence of biology.

Nasa scientists are in no doubt that Webb will fulfil its promise.

"I have seen the first images and they are spectacular," deputy project scientist Dr Amber Straughn said of Tuesday's further release.

"They're amazing in themselves just as images. But the hints of the detailed science we're going to be able to do with them is what makes me so excited," she told BBC News.

Dr Eric Smith, the programme scientist for the Webb project, said he thought the public had already grasped the significance of the new telescope.

"The design of Webb, the way Webb looks, I think, is in large part the reason the public is really fascinated by this mission. It looks like a spaceship from the future."

|

|